|

|

Table of Contents: |

|

CHAPTER 1

NewYork City 2008

“I just put hairspray on my armpits,” Carrie said. She told herself the shrill note in her voice was not hysteria. She was not losing it; she had merely chosen to call her ex-fiancé to tell him a funny story. He was one of her very best friends, and you shared the good stuff with your pals. “I was going for the deodorant. I kept thinking, ‘Wow, this deodorant is sticky.’ Then I looked at the can. The thing is, I don’t know why I had hairspray—I never use it. It makes my hair look like a Brillo pad.”

“Carrie? You okay?” Howie’s voice came at her over the phone. And suddenly she was going to lose it after all. How the hell do you thinkI am, Howie? My mother died ten days ago.Carrie drew in a deep breath. “I’m fine,” she said.

“You sure?” Howie sounded worried—and not quite awake. What time was it, anyway? “Why are you up at four-thirty in the morning?” he added, answering the question.

“Oh God, I’m sorry. I didn’t know . . .” Explanations raced through her head. See, Howie, I’ve been waking up a little early . . . No, the truth is, Howie, I can’t sleep. I can’t eat either—nothing except potato chips. I got into them when I was hanging around the hospital . . . She stopped herself. Because she was rambling. True, it was an internal ramble, but anytime she started wandering mentally it was a sure sign that she had lost control. And dwelling on the hospital and her mother’s last days there was definitely a bad idea. Carrie had gotten through the funeral Mass a week ago, and the memorial service the day before, by not dwelling. Not dwelling had gotten her out of bed that morning and it had gotten her dressed—except for the hairspray/deodorant mishap—and now she was on her way to clean out her mother’s apartment. Although possibly not right at this moment. Not at four-thirty am. “Go back to sleep, Howie. I’m sorry I bothered you.”

I am fine. I am Carrie Manning. I am thirty-seven years old. And, okay, I’m a little tense this morning because my mother’s ...not alive anymore. But I’m not going to dwell on that. Not now. Now, I’m going to think about how I got through the memorial service yesterday without crying once. I was great at that service. I didn’t even tear up when they sang the Panis Angelicus.“Carrie?” Howie’s voice on the phone brought her back to reality. “Honey, you’re not still freaking out about the flowers, are you?”

Okay, so I didn’t get through the memorial service quite as well as I might have.

“I didn’t freak out. I was upset.”

“However you want to say it, Carrie . . .”

“I put it in the obituary—‘No flowers’—that’s what it said. It was right there in the New York Times. I listed all of Mother’s charities so people could make donations.”

“Yes, I saw that.”“I did it exactly the way she wanted it. The woman was once voted Humanitarian of the Year by Living Life magazine. That’s what the plaque said: Rose Manning, Humanitarian of the Year, 1986 ...“Her wishes for her own funeral should have been obeyed. And I got it right. I got it goddamned right!”

“Absolutely.”

“Everyone knows how Mother feels about flowers. Especially roses. Why would anyone send her a basket of white roses?”

“I guess there was someone who didn’t know . . .”

“After the article she wrote about Guatemalan children? The one about the five-year-old kids who pick roses and wind up with respiratory diseases and blisters full of insecticides?”

“Sweetheart, calm down.”

“You know what Mother says every time she sees those cheap roses in the delis on the street. She carries her pamphlets in her purse so she can show the owners—”

“She carried them.”

“That’s what I said.”

“No, you said she carries them. Wrong tense, Carrie.”

And suddenly it was real—in a way that it hadn’t been at the memorial service, or at the funeral Mass, or at the mausoleum. Now there was no way not to think about it. Her mother was gone. And Carrie was an orphan. The room went cold. There was a lingering scent of hairspray in the air.

“Carrie? Would you like me to come into the city and stay with you until my first appointment?”

“No. Thank you.”

“I could bring you some coffee—from the diner on the corner, all black and bitter. None of that Starbucks-wannabe stuff.”

“You’re the best ex on the planet—but I really am okay. And you need to get your sleep. You probably have a gazillion root

canals today.”

“Only one.”

“Go back to sleep. You’ll need steady hands.”

And I need to get through this without dramatics.

That was what her mother had called it when Carrie was a kid and her mother thought she was getting too worked up about something. “You’re being dramatic, dear,” Rose would say. “Are you sure you’re not trying to draw attention to yourself? That’s ego, Carrie, and you must never indulge in ego. The nuns tried to teach me that when I was your age, and I wish I had listened. Just remember, you and I are just ordinary people.”

That had been a lie. Carrie’s mother hadn’t had an ordinary bone in her body. If you looked up “not ordinary” in the dictionary you’d find a picture of Rose Manning. And she never had to try to draw attention to herself—it came to her automatically. For years it was her looks that did it. When she was young, Rose Manning’s beauty was almost unnerving. Carrie closed her eyes and pictured her mother: the tall, slender body made for fashion—although by the time Carrie knew her, Rose was no longer wearing couture— the huge, green almond-shaped eyes, the high, sculpted cheekbones, and the creamy skin. Rose’s thick red-gold hair was always piled in a shiny mass at the back of her head, her mouth was delicate but somehow still full, and her nose was aquiline perfection. When you put the whole package together you got a mix of ethereal and elegant that stopped conversations. And the magic had lasted for decades. When Rose died she was sixty-four, and until her last year when the cancer finally took over, she could still silence a room just by entering it.

But Carrie’s mother had always been more than just a breathtakingly pretty face. She had possessed an internal power her daughter could never define or understand. Wearing one of her interchangeable skirt-and-blouse ensembles—she never spent time on wardrobe—and exhausted from a night spent volunteering at her homeless shelter, Rose could glide into a board meeting packed with Wall Street sharks and dominate. Carrie opened her eyes.

“Is it pretty out there in Katonah?” she asked Howie. She and Howie were both city people, but after Carrie had canceled the wedding, he’d relocated to the suburbs, saying he’d needed to move on. Carrie couldn’t imagine anyone voluntarily not living in Manhattan, but since he was her friend—thank you, God, because she wasn’t quite sure she could handle it if he weren’t—she tried to be supportive. “I bet it’s pretty out there,” she repeated.

“It’s hard to tell; it’s still a little dark outside.”

“Was it pretty last night before you went to bed?”

“I guess,” Howie said. “There’s a big bush on my front yard that was there when I bought the place, and it’s starting to get all these yellow flowers on it. The guy across the street says it’s a forsythia.”

“I’m glad you’re happy, Howie.” And she was. Truly. Even though it ached a little to think that he could be happy without her. But that was only natural—right? The real point, the thing to focus on here, was that he was still her friend, that he had understood that she backed out of marrying him for his own good, because emotionally speaking she was a disaster on two feet and she didn’t want to inflict the train wreck that was her life on him. Howie, bless him forever, had understood the backing-out thing for the act of love that it was. “I mean that—about me being happy you’re happy, Howie,” she added.

“Thanks.” He paused for a second, then chose his words carefully, “Listen . . . sweetheart, why don’t you hold off on clearing out your mother’s apartment for a few weeks? Give yourself a break.”

Because if I don’t do it right now, I’ll never be able to.

“I’m cool. Really.”

“Of course you are!” he said, way too heartily. “I know that!”

“Thanks. Night, Howie . . . well . . . good morning.” She started to hang up, but his voice stopped her.

“Carrie?” he said. “You did get it right, yesterday. You got the memorial service right.”

“Thank you,” she said as she put down the phone. But Howie was wrong. Carrie’s eyes shifted over to the doorway, where the basket of white roses sat on the floor.

“Would you like these?” the priest had asked her after the service was over. What she should have done was to tell him, vehemently, to toss the basket into the garbage. But the flowers were lovely, a soft off-white with just a touch of pinkish blush at the heart. In the days since Rose had died, there had been many speeches given about her. Her memorial service had been packed with people who had admired and respected her. But, per her instructions, there had not been one personal touch, not one moment in which anyone acknowledged that Rose Manning had been more than an icon, that she’d also been a widow, a daughter, and a mother. No one had thought to say good-bye with something extravagant and beautiful—except the clueless sender of the white roses.

“Yes, I want them,” Carrie had said to the priest, and she had taken the basket out of his hands and brought the roses home.

I failed you, Mother. I’m sorry.

carrie stumbled through the obstacle course that was her bedroom. When she’d finally left her mother’s apartment in her late twenties, she’d been determined to create a cozy space for herself, and she’d splurged on several large, cushy pieces of furniture. Unfortunately, she had not measured the size of the rooms in her small home. The monster bed ate up almost all of the floor space in her bedroom, so opening the bottom drawer of the bureau was impossible unless she was squatting in the closet. For bedding, Carrie had purchased eight white pillows and a white down-filled comforter. She’d been going for Sensuous Luxury; her best friend, Zoe, said she’d achieved Marshmallow Blob.

In the living room were more puffy oversize chairs, ottomans, and a sofa. Someone had told Carrie that putting a mirror on the wall above the sofa would make the room look bigger, and she had dutifully done so. The bottom of the mirror frame jutted out from the wall, so when guests sat on the couch they had to slouch or risk losing a piece of scalp.

Carrie carefully threaded her way to the bathroom. She looked at herself in the tiny mirror. She was not the beauty her mother had been, but that was not something she obsessed about. As Zoe once said, who the hell was as beautiful as Rose? Even in a time when any woman with enough cash could buy the nose and boobs of her dreams, Rose had been in a class by herself. On the other hand, Zoe had continued kindly, Carrie wasn’t exactly a disaster. At five-four, she was cute rather than regal, but she was endowed with fairly impressive cleavage, and her legs were truly fine. Her nose might have been a little too long, her dark brown eyes were probably too deep set, and her curly hair—also dark brown—was always a mess by three in the afternoon. But her smile was fabulous. When she unleashed it. “Which you don’t do often enough,” Zoe had said, wrapping up her assessment. “You can’t get away with your mom’s ice princess act. And it wouldn’t hurt if you used a little makeup.”

Carrie searched around in her medicine chest and finally unearthed some seldom used blush and mascara. She found her lip gloss in her purse, managed to stall another minute or two with it, then went into her kitchen and dawdled over her breakfast quotient of sour-cream-and-onion-flavored chips. But it still wasn’t six o’clock yet. For some reason she didn’t want to go to her mother’s apartment before six o’clock. On the other hand, staying in her own apartment was out of the question. There was only one person Carrie knew—except for poor Howie—who’d be awake at this hour. Carrie put on her coat and headed out the door.

zoe was already up and working when Carrie rang her buzzer. Carrie knew this because when Zoe answered the door she was wearing her work clothes—flannel pajamas with red roses on them and an apron liberally smeared with chocolate—and her blond hair was bundled up under a net. Since Zoe was six feet tall and skinny, the look was distinctive. She stood in her doorway peeling off a pair of surgical gloves and eyeing Carrie with the look of sympathy and concern that everyone had been giving her for the last year.

“Hey, Carrie. Are you—”

“New rule,” Carrie broke in hastily. “Don’t ask me how I am, okay?” Zoe started to speak, then thought better of it. “And we’re not talking about memorial services, or funerals.” Or mothers.

Zoe nodded. “Can I ask why you’re here?”

“Not really.”

“Okay. Come into the kitchen.”

Actually, Zoe’s entire apartment was a kitchen. She’d stashed a cot in one corner of it, and there was a closet where she kept her wardrobe, but the rest of her small studio had been gutted and fitted out with two industrial-size refrigerators, a restaurant stove, a large table at which two people could work comfortably, and several huge storage bins full of sugar and cocoa. Stacked against one wall were shipping supplies, rolls of gold tissue paper, and cases of hand-painted candy boxes. Zoe was a candy maker who sold herb-flavored chocolate truffles to the hippest gourmet groceries and restaurants in Manhattan. Since five that morning she’d been taking baking sheets covered with little frozen balls of the chocolateand-cream mixture known as ganache out of the fridge and dipping them into melted bittersweet chocolate—the best Belgium had to offer—before dusting them with cocoa. The ganache had been infused with a variety of flavors such as lavender and rosewater, and in the case of one client—a Mexican restaurant—hot chili peppers.

Carrie knew all of this because for two years she too had stumbled out of bed at the crack of dawn to dip and dust truffles. That was when she had been Zoe’s partner in the business—a business they had started together and worked on happily, until one day Carrie felt the walls start to close in. She’d begged Zoe to please understand that she still loved her but there had to be more meaning to life than candy. Zoe had argued that they were on the verge of landing their first big account with a chain of trendy Manhattan grocery stores, which they had both busted their buns for, and Carrie would be ripping herself off if she sold out. Carrie couldn’t explain why she had to dump the business which had been her idea in the first place. She just knew if she had to wrap one more truffle in one more piece of gold tissue she was going to start throwing pots of chocolate around Zoe’s apartment. She’d left the business, and six weeks later, Zoe, as sole owner, had landed the coveted account. Now Zoe could afford to hire people to help with the wrapping, although she was still doing the dipping and the dusting herself. And soon she’d be reclaiming her living space because she’d be renting a professional kitchen in Brooklyn.

As Zoe swirled the first of the truffles in the coating, the hot chocolate released a whisper of a scent from the frozen ganache. Carrie sniffed the air. “Basil?” she asked.

Intent on her candy, Zoe didn’t look up. “It’s still the most popular flavor,” she said. “Bean and Brown can’t keep it in stock.” She placed the coated truffles on a piece of parchment paper and prepared to start rolling them in the cocoa.

“Hang on,” Carrie said. She opened the cabinet under the sink where the hairnets and gloves were kept, and suited up. “It’ll go faster if we work together.”

Zoe threw her a funny look, but mercifully she didn’t say anything. They worked side by side in silence, falling into the familiar rhythm they’d established over so many mornings, until five cookie sheets covered with finished truffles were back in the fridge. “You still have the feel for it,” Zoe said as they stripped off their rubber gloves. “You know how many people I’ve hired and fired over the last four months because they didn’t have the touch?” She hesitated, then said, “You know . . . if you wanted to, Carrie ...you could buy back in.”

There were a lot of people who would have been pissed about the way Carrie had split right before their big contract came through. But Zoe had known Carrie since they were in grammar school and she understood Carrie’s problem with follow-through. She’d watched Carrie start and abandon a dog walking service, a vintage clothing store—this was with another, less understanding partner—and a brief, horrific career as a personal assistant. Now Zoe eased herself onto one of the stools that flanked the worktable. “I’m serious,” she said. “Would you like to come back?”

For a moment it sounded wonderful. For the last year, most of Carrie’s time, to say nothing of her available brain space, had been spent caring for her mother. Rose’s doctors had admitted early on that there wasn’t anything they could do for her, and faced with that reality, Carrie had set out to make sure her mother’s death was a “good” one—even though she wasn’t sure she believed there was such a thing. Rose had stayed in her own apartment for as long as the medical professionals would allow it, because that was what she had wanted. Only her last two weeks were spent in the hospital. The ordeal had been so absorbing that once it was over, Carrie had found herself with endless hours she couldn’t fill. And she’d never felt so lost in her life. If she went back into partnership with Zoe, she’d have work, and a place to go every day, and ...And after two weeks she knew she’d be begging to get out again.

Something ragged and painful started growing in Carrie’s chest. “The business is big now. It would be too expensive for me to get back in,” she said.

“You’d pay what I did when I bought you out.”

The ragged something moved up into her throat. “You’re being too nice to me,” Carrie mumbled. And she wanted Zoe to please, please stop. Because she couldn’t take nice right now. Nasty she could handle, but nice was going to make her lose it.

“Why the hell would you want to work with me again?” she demanded belligerently. “I’ve messed up everything I’ve ever tried. I washed out of college; I didn’t make it through six months of culinary school.”

“But you came up with a great recipe for basil truffles—”

“I’ve had God knows how many jobs and I’ve quit every one of them. This candy thing is the third business I’ve tried and dumped. I couldn’t even hang in with Howie and he’s got to be the sweetest man in the world. I am a complete and total screwup, and . . .” she stopped herself. “And why aren’t you all over me right now?”

“Why would I do that?”

“I’m whining and wallowing. Why aren’t you busting me for having a pity party? That’s what girlfriends do—we bust each other. Why aren’t you telling me that I made those choices and I need to take responsibility and grow up, like you always do?”

“Old rule,” Zoe said softly. “A girlfriend doesn’t bust a friend whose mother has just died.”

So Carrie finally lost it. She cried loudly for a long time. After she finally finished, Zoe pointed out that was probably the reason why she’d come over. “And you had mommy issues even before Rose died,” she added.

“Not anymore,” Carrie said.

“They’re probably worse now that she’s gone. You never got it all cleared up with her, and you need to do that. You know?”

Carrie did know. But she didn’t want to start sobbing again. “Unfortunately it’s going to be hard to have a nice long talk.”

“You need closure, Carrie.”

“You really should stop Tivo-ing Dr. Phil. And for your information, I’m getting closure. I’m going to the apartment today to clean it out.”

“Alone? Don’t do that.”

“Why does everyone keep saying that? I can handle it.” Zoe looked at her. “I’m okay. Okay?”

After a second, Zoe nodded and pulled another tray of basil truffles out of the freezer. They dipped and dusted until it was nine o’clock and there was no way Carrie could tell herself that it was too early to go to Rose’s apartment.

“can i ask one question about the memorial service?” Zoe said as she walked Carrie to the elevator.

“Can I stop you?” Carrie braced herself for another Dr. Phil moment.

“Did you invite your grandmother?”

The question was a little worse than Carrie had expected. “I couldn’t,” she said after a moment. “Mother wouldn’t have wanted it.”

“Do you think your grandmother would have come anyway?”

“Why?”

“I thought I saw someone in the back ...she looked a little like some of the pictures I’ve seen ...from the end of your grandmother’s career.”

“The way I understand it, if she had shown up we would have known it. At the very least there would have been an entire brass section.”

“That sounds a little hostile.”

“It’s just a fact. Everyone says no one could milk an entrance like Lu Lawson.”

Read Chapter 1 of The Three Miss Margarets.

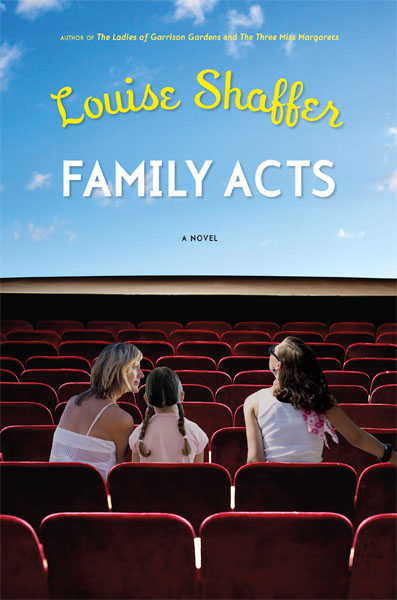

Read Chapter 1 of Family Acts

Read Chapter 1 of The Ladies of Garrison Gardens

Order Looking For A Love Story